My

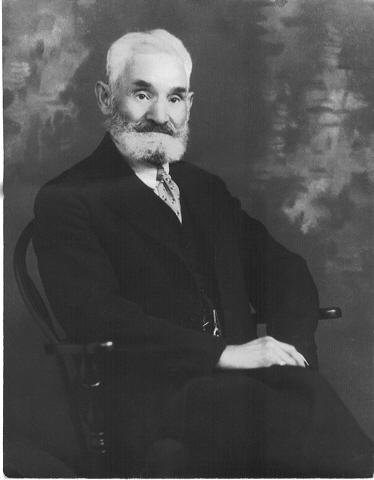

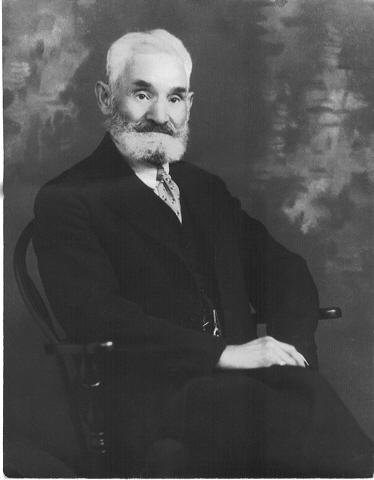

great grandfather, Naftali Linger

My

great grandfather, Naftali Linger

(my mother's mother's father)

| Autobiography of Norman Koren | Home

Summary and early years |

I'm writing this rather lengthy autobiography for my children, family, and friends, as well as for my own therapy. I wish my father had done so for me. Too many good stories have been lost. Maybe better stories than mine, but it doesn't matter. I need to pass mine on. And since I don't plan to publish beyond an unpublicized website, I can say almost anything I want. I can ramble, digress, philosophize, and pontificate. So here goes...

My

great grandfather, Naftali Linger

My

great grandfather, Naftali Linger

I always knew my father's father as Julius Koren, but he appears in a mysterious Internet post as "Yidel," and in the Ellis Island records as "Idel." He was one of ten children, and he was a hard man. When my father was little he saw the first airplane to fly over Rochester (around 1909 or 1910) he ran inside to tell his father what he'd seen, and got soundly spanked for lying. When he wanted a winter coat, his father insisted that he get the heaviest available overcoat-- the type worn in the old country. Very oppressive and extremely unfashionable. It must have made him the butt of jokes. When my father wanted to go to college, his father said, "Learn a trade. Then you can do whatever you want." My father became an electrician and never went to college. This was uncharacteristic of Jewish families and a sadly lost opportunity. In his later years, my paternal grandfather became misanthropic and reclusive. One of the most embarassing moments of my life was when my eighth grade teacher told me she had met my grandfather and I replied that I had no living grandparents. I had forgotten him even though he lived just four blocks away.

My maternal grandfather, Harry Nathanson, couldn't have been more different. He was socially gregarious and had a great many friends. My cousin Dan Levin recently told me an intriguing tale about him. In the 1930's he operated a small pasta factory called "Nathanson's Noodles." Because he was a good hearted socialist, he was lax at collecting debts (and there were many who couldn't pay in those depression years), so he soon went out of business. My parents never spoke of it, perhaps because I grew up during the McCarthy era when there was a real fear of being associated with communism. My parents succumbed to that fear. They had little to say about the past. That's why I'm writing this.

When I knew my grandparents, they were retired from full time work. But my maternal grandparents had a part time business: catering. Most of the ground floor of their house on 5 Morris Street in Rochester's old Jewish neighborhood was a hall with a wooden floor mostly devoid of furniture. From time to time they hosted community affairs like weddings and bar mitzvahs. The customers must have been relatively poor Jews because most of my parent's generation were well on the way to the suburbs by then. I have a few memories of these events: my mother cooking chickens on the old-fashioned gas stove (would now be a treasured antique) and klezmer music. Songs like "Tzena, Tzena." The klezmer revival that started in the 1980's brought back many fine memories. I hadn't heard klezmer in over thirty years. I didn't even know the word "klezmer."

My most vivid memory of the old house was my father, my cigar smoking

uncle Joe Goldman, and my pipe smoking grandfather playing pinochle on

a card table at the end of the hall closest to the kitchen. I never learned

pinochle. My grandparents living quarters were sparse, consisting primarily

of their dimly lit bedroom. My grandmother did most of the cooking-- very

traditional. My grandfather made special treats-- kinshes (potato and meat

dumplings in a pastry crust) and teglach (something like croutons held

together by honey; very messy but very delicious).

Dan's father Morris Levin brought his father-in-law (my great grandfather) Naftali Linger to Rochester from a village or Shtetl called Orinin, in the state of Podolia in western Ukraine. (Dan pronounces it "Ah-ryn-yen." My cousin Beverley Wiseman Markowitz recently sent me a copy of a remarkable memoir, "Orinin, My Shtetl in the Ukraine," by Beryl Segal, from the archives of the Rhode Island Jewish Historical Association.) Upon his arrival he was installed in a spacious basement apartment in the Rose Lea Apartments that Morris owned, to act as the superintendant."Oy America, America, indeed the golden Medina where I can live in a building owned by my son-in-law and collect rent and be in such an esteemed position." He was active and independent and determined to be the head of the family. This entailed walking each morning five miles each way from the gentile Parsell Avenue and Culver Road to Joseph Avenue, the intensely Jewish neighborhood where most of the immigrants worked in the men's clothing industry. (Hickey-Freeman is a venerable Rochester institution. I worked there for a few days one summer as an electrician's apprentice.) Unfortunately this meant crossing the wide square known as the public market. Here Polish and Italian stalwarts worked as stevedores unloading shipments of produce. The sight of a handsome full bearded Jew crossing their territory was irresistible. They committed the ultimate insult and tried to pull his beard. The phone call came to Dan's father.

"Morris, this is O'Reilly, down at the jail. We have your father-in-law here."

"What are the charges?"

"Assault and battery. We have one Bonomo and one Pulsutsky at Genessee Hospital. Nothing serious."

"No problem." A quick call to Joe Blockstein, the alderman, and he was promptly released.

"Oy America, America. In Russia it would have meant Siberia," Naftali marveled.

Another story about your great grandfather. We children were treated to what was to us the most fantastic sight we had ever seen. To this day it stands out to all of us. With great ceremony we would gather around our grandfather and plead with him to put the plams of his hand together and show us a large crevice, a gash, that ran from one hand to the other.

"Well," he explained in Yiddish, "I was working in my shop (he was a carpenter) when I heard a scream from the front of the "stubeleh." It was your grandmother. There, standing over her was a Cossack with a sword raised over his head. I didn't need to ask any questions about what he wanted. Bubbeh (grandmother) was a beauty. I grabbed the sword with both hands and took it from him. Naturally he ran. Wouldn't you? Well, it turned out to be a blessing. What's a Cossack without his sword? He came back the next day and we made a pact that the cossacks would never harm us if I returned the sword and never told his friends about the incident. We shook hands, and despite the pain it caused me it was the sweetest handshake I ever had."

How Morris (Dan's father) came to this country was the triumph of self-preservation over patriotism. The Czar of all Russia had devised a system, though he didn't know it, that would have served Hitler's purposes years later, ridding his country of a large portion of its Jews. It was "the draft," and it was no ordinary draft: it entailed twenty years of service in Siberia. Morris was no fool and he did the sensible thing. He ran. If he'd chosen to stay I would have now been "frozen sperm" buried in the Steppes of Russia.

Aunt Tilly (my mother's sister) was one of those unfortunate beings whose physiology was her greatest obstacle to her chosen "ART." She longed to be a ballet dancer and joined every group who would have her. Her idols were Isadora Duncan and Ted Schawb. Oh yes, the obstacle. She was shaped like the Michelin Tire woman: short, painfully fat, and awkward in every department except her heavy arms and graceful hands. Out of loyalty we attended every recital, the parents up front and the rest of us hiding in the last row. BUT we loved her. Her husband (Joe Goldman), of blessed memory, loved her and supported her. Although they were only related by marriage, he looked exactly like his father-in-law, like the son they never had.

My

father David Koren

My

father David Koren

My father, David Koren, was born in 1904 in Zhitomir, a Ukranian

city 130 kilometers west of Kiev, and immigrated when he was around four.

My mother, Jane Nathanson, was born in 1905 and immigrated when she was

two. Both my parents grew up in Rochester, where they received high school

educations. My mother was trained as a hairdresser but I never remember

her working in that capacity. I don't know much about her life before I

was born. I sometimes heard her talk about working at a restaurant called

Cohen's, probably in the 1920's. It must have been an immigrant hangout.

I can only imagine.

My father had an interest in race cars when he was young-- I think he worked on them as a mechanic. He was very handy. I remember seeing some photographs, but I never found them after he died. He lived in New York City in the late 1920's. I imagine he led a rather wild life, something along the lines of Henry Miller's Tropic of Capricorn, though not quite so wild. He occasionally hinted at his youthful adventures, but I wasn't ready to hear about them until it was too late. He lost his job immediately after the stock market crash of 1929 and returned to Rochester. He told me that after New York, Rochester was so quiet he couldn't sleep for three nights.

The one story I remember from the 1920's-- the age of prohibition-- was that my father tried his hand at smuggling whiskey from Canada. On one of those trips back from the St. Lawrence River he was chased by the mob through the Adirondack Mountains at night. Fortunately he had the presence of mind to turn off his headlights and make a quick turn on a side road. The mob car sped by. My father never ran whiskey again.

My

mother and grandmother

My

mother and grandmother

taken in Buffalo, NY

around 1909

My parents were married and divorced in the 1930's. They remarried in 1940, when the depression was finally ending and my father could afford to buy a house. My parents never said much about the divorce. The only grounds for divorce in New York State at that time was adultery. It was often staged. I think the real reason was that my father didn't work much in the 1930's, so they had to live with my mother's parents. I remember my grandmother as a charming old fashioned woman with old world mannerisms. But she must have been meddlesome and difficult to live with. She was the consummate back seat driver. I remember her as a faithful fan of Ed "Soloman's" TV variety show, which was very big in the fifties and early sixties. Elvis and The Beatles appeared on it early in their careers. Nobody had the heart to tell her that his real name is "Sullivan," which isn't exactly Jewish.

I asked my father what he did during the depression. His reply was, "I played poker for a year and kept losing. So I went to the card room for a year and watched and learned psychology. The next year I won consistently." That accounts for three years of that long impoverished decade, which left deep emotional scars on both my parents.

My father worked as a journeyman electrician from as early as I can remember until he retired. He was a member of IBEW (International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers) Local 86. The only exception was a few months in the early 1950's when he worked as a manager at Royalite Electric Supply. He promptly got an ulcer and went back to being a journerman. He liked working with his hands; he was good at it, and union electricians were well paid. Our standard of living was middle class, but my father's mentality was distinctly blue collar. I experienced that mentality when I worked as an electrician's apprentice for two summers while I was in college. Some of my co-workers were decent salt of the earth types; others were plain vulgar. I didn't fit in.

In the late 1980's I went to see a psychic in Del Mar, California to learn why I couldn't find a good relationship with a woman. She started by saying, "We need to talk about your father. He was the ultimate non-risk taker." At the time he was the furthest thing from my mind, but what she said was terribly true. It stuck. His reluctance to manage and take risks are handicaps I've had work hard to overcome, and I can't claim total success. The psychic did a ceremony to exorcise my father's presence from my mind. I didn't feel any change.

| Next: Summary and early years |